by Bethan Jones

Within fan communities, fannish norms, rules and behaviours have been discussed for years. Many fans are used to their topic of interest only being shared with a small number of people – their fellow fans, sometimes family and friends. But the number of more public stories about fans are on the rise. Fan studies as an area of serious academic analysis has been growing since the early 90s, and press interest in fans have been increasing year on year since at least the 2000s.

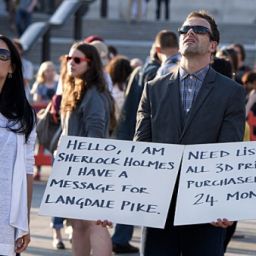

Interest in fandom and fan activity has been on the rise in the mainstream press over the last couple of years. Articles appear talking about fan studies as an ’emerging field’; magazines like The New Statesman analyse fan responses to Sherlock; and news sites like the BBC feature stories on how fan fiction is our new folklore. This more public interest is then focus of much discussion in fandom and academia, particularly when the (often unspoken) rules of fandom, like not making actors a

Two such instances are the topic of this article: what has become known as ‘Morangate’, where Caitlin Moran asked actors Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman to read from a piece of Sherlock slash fic at the premiere of The Empty Hearse, and ‘Theory of Ficgate’, where as part of an extra-curricular module on fan fiction university students were asked to leave critical comments on selected pieces of fic. While these instances are different regarding the fandom communities concerned – addressing slash writers in the audience and introducing students to the academic study of fanfiction – the end results were the same. Fans felt intruded upon, mocked and pathologised.

Fans are familiar with being pathologised– for fandom. However, the stereotype of the lonely geek in his parents’ basement or the stalker fangirl are slowly being replaced by analysis of fan responses to Doctor Who and the role that fans play in the revival of old texts. This new found interest and grudging respect, can be gratifying, but as ‘Morangate’ and ‘Theory of Ficgate’ demonstrate, this research – both by the popular press and inside the academy – has an impact on fans.

The fic Caitlin Moran asked Benedict and Martin to read was a piece of slash, written by a Sherlock fan and posted to fanfic archive Archive Of Our Own (AO3). In response, the fanfic writer shared a public post on Tumblr in which she talked about the effect of the event had on her – how she felt she was shamed for writing fan fiction, and more specifically erotic fan fiction about two fictional men.

The intention of the “comment on fanfic” assignment was to share a love of fan fiction, but the comments left by the participants in the class on the selected fics were, at times, condescending and borderline rude, showing no awareness of fannish norms and codes of conduct. Of course, the question many people will ask at this point is ‘so what?’.

Why do these particular scenarios and these particular fans deserve special consideration? This is a question we have to ask ourselves as fan studies scholars; it’s a question I ask myself whenever I do research. I don’t know that it necessarily has an easy answer, but I think it is inherently tied up with power and ethics and accountability.

What is crucial in both ‘Morangate’ and ‘Theory of fic gate’ is that none of the fans were asked permission for their involvement, and none of the instigators considered the effects on the fans. In other words, the fans were acted upon rather than able to determine their own actions. They were forced into the situation of having their work read and mocked, and having rude and unnecessary comments posted on their stories. In fandom and academia, one of the central issues debated in relation to these events was what constitutes private and public in the age of social media. The lines between these become increasingly blurred, as Angus Johnston writes:

The reality is that the boundary between private acts and public acts is blurry, and always has been. People do private stuff in public all the time, and while we often have a legal right to violate the privacy of those moments, mostly we don’t, because it’s understood that we shouldn’t. It’s understood that it’s a jerky thing to do.

A woman talking about an abortion with a friend in a café is a private act in a public space. A parent dealing with a toddler having a meltdown at the grocery store is a private act in a public space. We understand that recording these conversations to play in a pub later is something we shouldn’t do. Where the internet is concerned, we are still finding our feet. However, Twitter, as is Tumblr, is designed to be a public space. Users on each are able to password-protect their accounts to restrict who can see what they post, but the overwhelming majority of posts are open, searchable and shareable. In that sense it is perhaps easy to understand why a celebrity might think it okay to search for fanfic, or undergraduates to comment on fic.

As Kristina Busse notes, however, “simple dichotomies of private and public spaces seem to fall short of the more complicated realities of current social media experiences.”

Tumblr users can regard their posts as semi-private because they are speaking to a specific audience, in this case of fellow Sherlock fans, within a specific community which typically doesn’t receive much attention outside of the fandom. The Moran-used fic was thus posted as a private act in a public space, and Moran should not have shared that conversation.

What is murkier in ‘Theory of ficgate’, however, is the replies left by the Berkeley undergraduates on fic posted to AO3. Like Tumblr, AO3 is a public forum. It is not necessary to have an account there in order to leave kudos for writers or to post a comment. Members of the class, however, were required to create new accounts on Fanfiction.net and A03 for the purpose of the class. Additionally, one of the class requirements was to post weekly reading reviews:

To show completion and comprehension of the readings, students will be required to submit a review on the last chapter assigned for each reading assignment. To receive credit, students must screen shot these reviews and email them […] no later than 5pm on the day prior to their relevant class.

Unlike Moran, then, who took fic from a fan archive and shared it to a wider audience, the Berkeley students were required to leave critical reviews on fic within the fannish community.

To return to my earlier analogies, we understand that joining the conversation to give our views on abortion, or interrupting the parent to critique tone of voice is something we shouldn’t do. These would be intrusions upon a private act even though that act takes place in public. Students in the Berkeley class, many of whom were fans themselves, entered fandoms that didn’t belong to them and posted critical reviews, rather than the softer ‘concrit’ that fannish norms dictate.

One of the students, in a blog posted after the class had ended wrote:

The main problem is that authors were receiving unsolicited critical comments from people outside of their fandom. […] The assignment to leave concrit has been completely discontinued. I realize this left many authors feeling attacked and unsafe— some students have expressed discomfort with the task as well— and I do want to formally apologize. Second, regarding the fact that students are reading fics outside of our fandoms, facilitators have changed the assignment accordingly. The original syllabus listing was organized by fanfic tropes, such as Alternate Universe, Crossovers, and our reading list now extends to fics within the student’s chosen fandom, so we may have appropriate context and knowledge of source material.

What neither Moran nor the course facilitators considered were the people behind the words were affected by seeing their work torn apart suddenly in public or a site they consider to be a safe space.

These actions are born of a privilege which sees the instigators’ actions – the laughs they’ll get from seeing a fic read at a BBC event or passing a course – as more important than seeing the fans as actual people with feelings. It comes from a privileging of the text before the person. Explaining the rationale behind the permissions policy in the journal Transformative Works and Cultures, Kristina Busse and Karen Hellekson write

The general academic response in literature and media and film studies (which is where most academics citing fic would come from) is that texts are treated as independent of their authors. […] In contrast, we […] consider ourselves fans first. […] We are very, very concerned to ensure the privacy and security of fans and have given much thought to ethical considerations.

Typically in the humanities the focus is on the text. We perform textual analysis of books and films, and we think nothing of quoting an author without seeking their permission first. In the social sciences, though, the person is put first. It’s why we have ethics boards in universities and why we have to consider the repercussions for our research participants. There is not a simple dichotomy between social sciences and humanities, of course. My work falls squarely under the humanities banner, as done much fan studies, but we are asking permission of fans and seeking out ethical approval from institutions for our research. But privilege is still an issue which needs to be understood more fully in academia and we have to recognise the ways in which we, as well as the press, engage with fans.

To combat the privileging of the text before the fan we need to look at the culture that emerged with web 2.0: participatory.

This participatory culture is echoed in the name we give to the people we interview and survey – they are no longer research subjects but participants. Fans are participants in our research, and fans are engaged in participatory culture. If we want fans to continue engaging with us we need to be include them in our work and we need to do it ethically.

As a fan studies scholar, I believe that it’s important for research into fandom continues. I think fans can offer us insights into texts that literary studies on its own can’t; that modes of production and consumption are changing and fans are intimately involved in that; that fannish practices, behaviours and codes can offer us cultural insights.

And I think that both academic and popular study help us out with these things. Talking and writing about fans shouldn’t be done solely by the academy but researchers should ensure that fandom is researched ethically and fans are actually understood, not just examined.

The issues raised and lessons learned from ‘Morangate’ and ‘Theory of ficgate’ are still evolving. Both events raised awareness of attitudes to fans in wider circles: Moran’s actions were discussed in the mainstream press and the undergrad class was discussion by fan studies scholars. Fundamentally, these discussions contribute to the evolving nature of fan studies research and allow us as scholars to reflect on our behaviour and the effect it has on the communities we undertake research in, and often times are a part of. And just as us academics are driven by a love of our subject and become frustrated when we see it being treated lightly, so too do fans love their fandom and deserve our respect, not our laughter.

Bethan Jones is a lifelong X-Files fan and PhD candidate. Her PhD looks at cult TV, fandom and nostalgia, focusing on the X-Files and Twin Peaks revivals, and she has written extensively on fandom, gender and new media. Her work has been published in Transformative Works and Cultures, Sexualities and the Journal of Film and Television, and she was winner of the Missing Time category in the 2009 X-Files Universe fanfic writing competition.