By Allyson Gross

Fans are remarkably good consumers of content in already-codified, tight knit communities. To market something to fans is an exercise in adapting or channeling some aspect of the fan object or experience into the marketed product — knowing your target demographic is, after all, Marketing 101. It’s with this understanding that director Daniel Schloss and writer Charlie Sohne created Truth Slash Fiction, an in-production television series about boyband fans who write slash fanfiction, the fan practice of writing queer romantic fictional stories about characters and real people. The writers of Truth Slash Fiction quickly caught the online attention of the One Direction fandom, especially writers of slash fanfic about One D. Rather than the fateful meeting of target demographic and product, however, the virality of the show’s trailer on Twitter in the fall of 2016 was met with mixed, often negative responses by the fans of the British-Irish boyband. While One Direction fans served as the show’s inspiration, the majority of them also hated everything Truth Slash Fiction represented.

As consumers, we’re familiar with the myriad ways that fandom is marketed to the broader public. Beyond the easy thematic jump from boyband fans to boyband television, we’re even more familiar with less related cross-promotion between brands and produced media: It’s Captain America chasing Bucky in a 2016 Audi commercial, or Twilight inspired vampires in an earlier 2012 Audi commercial. For the purpose of analyzing fan response to the phenomenon, the most relevant distinctions to make are in 1. who is doing the marketing, 2. what the product is, and 3. the intended audience. To use the Audi commercials as examples, the Audi motor vehicle company marketed a product unrelated to the produced media (a car, an external good unrelated to the fictional worlds of Twilight and the Marvel Cinematic Universe) to the broader public utilizing the popularity of the movies featured.

In the realm of nonfiction, celebrity product placement, like a Diet Coke commercial starring Taylor Swift, is similar — while Swift’s music has nothing to do with carbonated drinks, her association with the product drives traffic, if not outright profit. We watch the commercial, featuring Swift being overwhelmed by a horde of cats, not because of an interest in Diet Coke, but because of a popular interest in her person. These examples, directly referencing or featuring sub/objects of fandom, are marketed towards their fans as well as the public. Whether or not I’m a fan of Taylor Swift, the commercial is still accessible to me as a viewer. There is, after all, nothing exclusive to the fan experience about a pop star drinking soda. Of the ways in which fan objects intersect with marketing, these are the most common examples.

To market a product towards fandom, however, is an altogether different phenomenon than the above. Where Audi and Diet Coke reference and feature popular media objects for broader promotional purposes, marketing towards fandom utilizes specific understanding of inner-fandom practice, and/or is exclusive in its fandom references. In short, it’s making jokes or references only fans would get through referencing fandom things. Furthermore, brands marketing towards fandom more often takes place on platforms like Twitter — as opposed to more broad-reaching, public-facing modes like television commercials — where fan communities already exist. As Twitter accounts provide brands with easily accessible, humanized online presences, the platform facilitates easy engagement across fandom and corporation. Brands are ultimately able to market to fandom on Twitter through engaging with them as if they were fans themselves.

In response to a July 2015 tweet from a Supernatural fan that “@Astroglide ships Destiel,” or the popular slash ship of Dean Winchester and Castiel, the lube manufacturer’s Twitter account wrote, “We really just want to see a scene where Dean tries to explain to Castiel what lube is. Gold.” The reference to fanfiction about the popular Supernatural pairing proved amusing for many fans. Fans engaging with the Astroglide account made both declarations of love for the brand, as well as suggestions for how to further engage with the show and its fans. As Astroglide continued to tweet about Destiel throughout the day, the account repeatedly referenced the success of its engagement with the fandom, at one point commenting, “letting Gabe log onto our Twitter account today was clearly a good choice #Destiel.” As marketing to Supernatural fans utilized exclusive fandom references, tailoring tweets to fans of the CW drama alienated the rest of its followers, and the account knew it. “All of our followers that aren’t Supernatural fans are so confused right now,” wrote @Astroglide, but the brand didn’t mind; Accompanying the tweet was a reaction gif of SNL’s Kristen Wiig crying over a photo of Supernatural star Jensen Ackles. That the Astroglide account continues to tweet about Supernatural and even live-tweet episodes of the series is a testament to the benefit of the online buzz that the engagement with the fandom produces. Though tweeting about Supernatural may not translate into offline purchases from fans of the show, it’s not for nothing that Astroglide now seems to be, according to one fan on Twitter, “the Lube of Choice for most DeanCas fics these days.”

When done well, marketing towards fandom can yield significant online social currency within the targeted audience. At its best, it’s amusing when an otherwise impersonal corporation makes what seems like an inside joke or reference to something you love; At its worst, it’s capitalism fishing for clicks in the guise of a social media manager trying to fit in with all the kids online. For some within the One Direction fandom, a hat tip from brands to the popular fan fictional relationship between band members Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson serves as a beloved testament to the reality of “Larry Stylinson”.

In response to a 2016 Instagram post from Styles of a “lonely buffet,” the Pizza Hut UK Twitter responded, “@Harry_Styles Louis will be back soon. Then you can all come to Pizza Hut for the greatest buffet on earth… #LouisYumlinson.” At the suggestion that Harry was “lonely” without Louis, fans responded with notes ranging from excitement that “Pizza Hut knows what’s up,” to declarations that “Pizza Hut is my new favorite pizza place now!” With over 15,000 retweets and over 13,000 likes, the original tweet by Pizza Hut was a one-off, humorous attempt by the brand to engage with a subset of One Direction fans — arguably, one of the largest fandoms on the platform — with the obvious intent to trend online. Fans’ amused response was ultimately predicated on the perceived mutual acknowledgement and understanding of the Larry Stylinson phenomenon. Larry was so real, it seemed, that even Pizza Hut could tell.

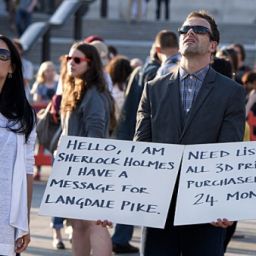

But what happens when the product being marketed to you is about you? Cue Truth Slash Fiction, the indie television series about boyband fanfiction. When the trailer for the television series first made the rounds on Twitter in September of 2016, One Direction fans who responded positively to the show’s premise expressed excitement over the recognition. More than just a one-off reference from a brand online, an entire television series was being shopped about their experience. In responses to the trailer on Twitter, excited fans wrote, “this is the story of my fucking life,” and tagged their friends with notes that there was “finally” a show that they could relate to. For some, the show was seen as a potential opportunity to normalize fandom practice. Despite initial discomfort, one fan on Tumblr wrote, “this might forces [sic] the public to realize, that a fandom’s fascination with slash fics is not the minority.” Better still, they continued, “this might be a powerful way of letting the world to know more about Larry.” But while the show intended to express an understanding of the One Direction fandom both on Twitter and in its product, the vast majority of responses ranged from wariness, to outright fear and distrust of the series and its intentions. Regardless of any effort expended by the Truth Slash Fiction writers to accurately depict and market a product for and about fans, to do so in the first place demonstrated a lack of understanding of the fandom itself. Even worse, by relying on fans to both promote and watch the show, Truth Slash Fiction cast its lot with a demographic that inherently mistrusted its product.

After the trailer for the series went viral in the fall of 2016, show producer Daniel Schloss tweeted, “Larries just lifted @truthslashfic to new heights causing #truthslashfiction to trend worldwide. The biggest and best fandom has our back.” Schloss rightfully attributed the virality of the show to Larries, a subset of the One Direction fandom oriented around the belief in a romantic relationship between Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson. As both the inspiration as well as the target demographic for Truth Slash Fiction, Larries were indeed responsible for the series’ online buzz. Why they shared news of the show, however, was based less in admiration than it was trepidation. Even within fandom more broadly, real person fiction (RPF) is still a comparably controversial topic in and of itself. For many fans, the potential exposure of the fandom to the broader public prompted fears of ridicule or abuse. As one of the top replies to Schloss’ tweet noted, “you better have our back and not make us look bad okay?” Though Schloss attempted to assure the fan by replying, “we got you,” the statement was less than satisfactory for fans who routinely experience online harassment for writing the very fanfiction that Schloss & Co. were hoping to profit from. While an understanding of fandom practice is crucial to successful marketing, Truth Slash Fiction’s best attempts still fell flat for their target demographic. Where, in the end, did they go wrong?

As Aja Romano wrote for the Daily Dot regarding a 2015 film of a similar topic called Slash, “the story of queer slash fanfiction is the story of women building a community of their own.” For men external to fandom culture to repurpose those stories or even attempt to retell them ultimately misses the point of these communities very existence. As one Tumblr fan wrote in a critique of Truth Slash Fiction, “it keeps coming back to agency and how WE DON’T HAVE ANY in this situation because they’re just using us for material without actually listening to us.” And although mainstream discussion of fanfiction has risen in recent years, it’s often underscored by a mischaracterization or derisive undertone toward the writers themselves. By depicting the One Direction fandom, Truth Slash Fiction bridges into the even more complicated territory of fans whose fan subjects are real people. By drawing more attention to One Direction fanfiction, the showrunners runs the risk of breaking the fourth wall, or the invisible barrier between fan practice and fan subjects. In a post with over 200 notes on Tumblr, one fan noted that drawing attention to the fandom felt like a violation of a protected community. The post concluded, “they’re threatening our safe space and the place that makes us happy because they want to make money off of us and exploit us and I will never be okay with that.”

Even worse, what fans deemed the most egregious example of exposing their engagement occurred while attempting to assure the fandom of the show’s intentions. In an interview with fan-based blog Head Over Feels, Truth Slash Fiction writer Charlie Sohne attempted to convey his understanding of the One Direction fandom by name dropping several works of fanfiction he had read in preparation for the show. By explicitly naming and even linking to certain works, the showrunners publicly broadcasted fan works not intended for public consumption, and faced the wrath of fans as a result. Three days after the publication of the interview, the official Truth Slash Fiction Twitter account posted an apology: “At the time, we assumed that complementing work was a universally positive thing to do — we now understand that was a wrong assumption to make.” With reassurances that they would be directly apologizing to the named authors, the apology missed the point. The showrunners’ publicizing of fan works in a non-fandom space to bolster their own credibility within the fandom not only betrayed the trust of potential viewers, but also made vulnerable the authors they attempted to compliment. As one fan noted in response to the apology on Twitter, “you’re putting a spotlight on a very intimate area of the lives of fans regardless.” Regardless of the fact that it technically existed in public online, fans were adamant that their fan practice was only intended for their community. By marketing their fandom for public consumption, Truth Slash Fiction made visible something fans never wanted to be seen. Before the show had even been sold, fans had already turned against it.

While tweeting fandom references, or even attempting to incorporate your brand into fan culture itself may be advantageous to one’s social media strategy, marketing a product towards fandom necessitates an understanding of fan communities. Particularly when relying on a single fandom to be both viewer, promoter, and serve as inspiration, such understanding is even more crucial. Beyond the semi-amusing clickbait of fandom-oriented tweets, constructing an entire product around fan practice for fans is tricky territory perhaps best left alone. Knowing your target demographic, it seems, may also mean knowing when to not engage in the first place.

Allyson Gross is a writer and climate justice organizer based out of New York. She is a recent graduate of Bowdoin College, where she wrote a thesis on One Direction and populism. Allyson can be found @AllysonGross, mostly tweeting about boybands, conspiracy theories, and Hamilton.

This is an interesting read! But since you did not link to the full interview we conducted with the creators, I want to point out that we, the interviewers, were the initiators of the discussion of specific fics. We’re fans and readers too, and always excited to swap recommendations and acknowledge really amazing fan works. Charlie was simply responding to our comments and bringing up pieces he had read and enjoyed too. As FANS we had no idea that discussing pieces would be controversial, though understand now that it could be distressing to someone not expecting it. But this wasn’t a case of the writers simply “name-dropping” titles to gain credibility. We also talked at length with them about their engagement with the fandom and the negative responses to the concept from people in the community. Cherry-picking from this conversation without linking to it mis-characterizes it, in our opinion. Here’s the full text: http://www.headoverfeels.com/2016/10/03/talking-with-the-creators-of-truth-slash-fiction/

Editors’ note: We’ve added in a link to the Head Over Feels podcast that was deleted from the original draft due to an editorial error.

Great article. I’d also add that Astroglide donated product to our 2016 Wayward Cocktails event for Supernatural fans at SDCC.