by Rosamund Lannin (@rosamund )

I met Neil Gaiman when I was 14 years old. He was doing a signing at Dreamhaven Books and Comics in Minneapolis, just over the river from my parents’ house in St. Paul. I was a regular at Dreamhaven – I went there as often as my paper route money and the Lake Street bus allowed. I bought my first Sandman comic there. Written by Neil Gaiman and illustrated by such luminaries as Dave McKean, Jill Thompson, Michael Zulli, and more, Sandman tells the story of Dream of the Endless, who rules over (you got it) the world of dreams.

Now, I’d always liked comics: As a kid, I read Batman and Superman and Betty and Veronica. As a pre-teen, I pored through my parents’ copies of Maus and Mad Magazine and old issues of the Funny Times. But Sandman: Sandman was different. Sandman felt like it had been written just for me.

Here was a story worlds away from capes and cowls and wholesome teenagers, or even snarky leftist broadsheets. Sandman was fairy tales and real people and a family as mythical and dysfunctional as my own. There were monsters in diners and magicians with pasts and ancient witch women who might step out of their New York apartments to help you on your quest. From the beginning, I was in love. I bought the first trade, then the second, and slowly amassed the entire series.

After Sandman, I moved onto his novels and short stories: Neverwhere. Angels and Visitations. The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish. Tales old and new and weird and real – they were exactly what I wanted, what I didn’t know I needed. I felt like Neil was writing just for me, and from the beginning he was Neil: although I knew little about the man behind the myths, I felt comfortable referring to him by his first name.

I got to the signing an hour early, and walked anxiously around the store. There were a lot of goths. I felt instantly uncool. I had that feeling, as I often did, that I shouldn’t be there: I was too young, too stupid, had too much color in my cheeks.

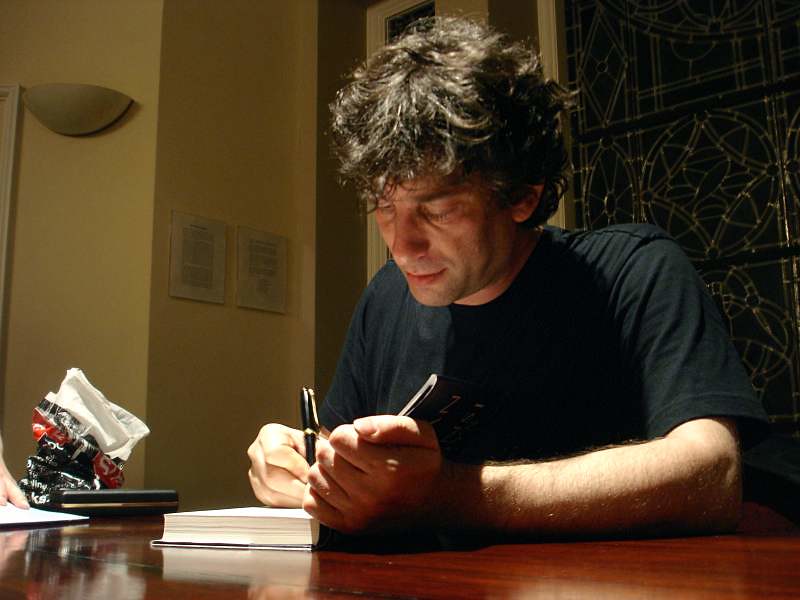

A dark-haired man entered the store and began to set up. I recognized him instantly (also, his face was on the back of the book in my hand.) My heart shot rays of adoration across the room, and at some point my feet followed: I shuffled forward, and placed a stack of books on the table. Neverwhere. Preludes and Nocturnes. The issue of Cicada which featured his the story “Troll Bridge”. 999: a horror anthology that was the reason for the signing. I should mention that the date was 9/9/1999, aka my birthday, aka my golden birthday. I was meeting my hero on my golden birthday.

I placed my books in front of him.

“Hello,” he said. He smiled.

I tried to smile back, looking not unlike a feral animal baring its teeth.

“Hi.”

“Oh, Cicada. I forgot that I did that story for them. I’m so glad you liked it.”

I nodded. I died.

He signed all of them, making sure to write something in each book.

For a week after the signing, I floated. I wanted to sleep for a week and dream of our exchange.

It is worthwhile to mention, in light of current events, that it is acting appropriately around a young girl should not be confusing or difficult. Be nice. Be kind. Do not treat her like a sexual object. When you are still forming as a person, it is everything when your hero regards you with respect. I am not saying Neil Gaiman should get a medal for baseline decency, but it did mean a lot.

In college, a friend of mine was Neil Gaiman’s personal assistant. Cody mentioned it casually and I lost my mind. I wanted to know everything, and harassed him for details. I found out some facts I already knew through the mid-2000s Internet: Neil Gaiman’s family had a history with Scientology, but Neil was no longer part of it and had not been for a long time. He had three children. He lived out in Menominee, which explained why the Wisconsin scenes in American Gods were so good. I gobbled up the gossip like candy.

I also found out some things you can’t find on the Internet, at least not without legwork. I am not going to share them, because being famous does not give strangers carte blanche to talk about your private life, and judge it accordingly – something many fans today seem to forget.

Neil Gaiman’s life was fascinating to me, but eventually I stopped my interrogations. I had other things to think about – like finals, and my job at the library, and making poor romantic choices.

Throughout college I continued to read Neil Gaiman’s books, recommend them to friends, and go to signings, but my love for his writing began to wane. I started to slowly lose interest after American Gods. I was lukewarm on Anansi Boys. I felt guilty for not liking it more, like I was betraying someone. I remember loving Coraline and The Graveyard Book, but eventually I stopped seeking his work out.

Around the time The Graveyard Book was published, Neil Gaiman began dating Amanda Palmer, lead singer of The Dresden Dolls. My interest in him flared anew. I did not approve.

I found out they were dating through the Internet. Some photo shoot they did together, and then I clicked and clicked and read and read until it was verified. This was the only way I would have found out: I did not actually know either of them or their friends, or run in any of their social circles. Cody was the closest I got to Neil Gaiman’s personal life, and ironically that sort of killed my interest.

Once he became a real person, poking into his affairs started to feel gross. Any excitement I had about knowing secret intel was outweighed by the knowledge that this was a real person, with a past and relationships and actual human qualities. It felt weird to know more when he was theoretically so close.

Disapproving of his romantic choices through a computer screen, though – that was okay. I was not a fan of Miss Palmer. I am not going to go into why, because my opinion does not and should not matter. You can love someone’s work or the idea of them as a person, and have a reaction to their choices, but there some thoughts do not need to be shared with a wider audience. Which is to say, I talked about it extensively with my friends, for years (!), but that was as far as it went. That was about as far as it could go, at the time – luckily, the Internet as we know it was still young. I was not aware that a person could air their gripes publicly in an online forum. Also, I like to think that even in my early 20s, when my id reigned supreme, I would have found taking it that far embarrassing.

In 2008, Twitter was in its infancy. Instagram was a twinkle in Kevin and Mike’s eye. Snapchat was so far away. It was not quite as easy to get minute-by-minute updates into people’s intimate lives. These days, I know practically by osmosis what Chrissy Teigen had for dinner (John’s oxtails and coconut rice looked amazing). And it’s fun, getting a sense of person whose work you admire. But there is a weird underbelly to knowing so much. Taking a deep dive into a creator’s personal life is now effortless – perfect fodder for a fanbase who believes that a steady stream of information gives them the right to comment on, and often rail violently against creators’ choices.

I want to be very clear that I am not talking about #metoo – sexual abusers should face not only fan backlash, but every legal consequence. I am talking about decisions that may be unpopular, but are not in any sense of the word wrong – and yet, fans treat the decision as such.

Fans behaving badly is not new. For as long as there has been celebrity, there have been reactions: in the 1960s, folk enthusiasts freaked when Bob Dylan picked up an electric guitar. In the 1910s, a riot greeted the debut of Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring”. Even before that, Arthur Conan Doyle was forced to bring Sherlock Holmes back from the dead after readers lost their collective mind.

The scene is never what it used to be, and artists are easy to blame. But there is something about the 24/7 access provided by the Internet that helps foster a false and dangerous intimacy between fan and creator: giving fans the idea that they, by the virtue of being consumers, have a say in someone’s personal life or the direction of their work. A few examples:

- SE Hinton, author of The Outsiders, was asked on Twitter if two of the characters in the book were gay. She responded honestly: “No. That’s not how I wrote it.” They dragged her for months – for not making their fan theory canon.

- Steven Universe fans bullied an artist to near-suicide for drawing a character too skinny. Not even an artist on the show – a fellow fan.

- They harassed an actual artist on the show as well.

- When Robert Pattinson began dating FKA Twigs, some fans were horrified that he was not dating Kirsten Stewart, his Twilight co-star. The Twilight “ship” not only never came in, but crashed into the very real iceberg of Robert Pattinson being a grown man with free will, not a receptacle for fantasties and bigotry.

- The reboot of ThunderCats had the power to ruin many adults’ childhoods. Most recently, Kelly Marie Tran of The Last Jedi fame deleting her Instagram due to fan harassment.

- Let’s talk about how the whole Star Wars franchise is a case study in toxic fandom.

There is no shortage of examples. Much of this behavior is based in misogyny and racism, some of it is not, and all of it seems to shriek, “You did not do what I want, therefore you are bad, and I am going to tell the world.”

This is not love. It is not even fandom. It is a mob.

I understand tying your emotions and identity to a body of work, and by extension the person who made it. Likewise, it is not bad to have an opinion, and share it. But giving your feelings outsize value, treating them as gospel truth, is where nerd culture continues to show its worst face.

When I was 14, I was very lonely. I had bad skin, few friends, and a home life rich in books but poor in boundaries. Neil Gaiman’s books were my escape, and what an amazing escape they were. They served as both trapdoor and ladder – they got me through and they got me out. And he, the person, was nice to me, in a time when the world did not seem very kind.

That means a lot. However, it does not mean that my opinion of life or work should carry weight any more weight than that of a fan – which is, after all, what I am. I am not his family, creative partner, or close friend. No amount of reading someone’s books, creeping their Instagram, or favoriting their tweets gives you a full and nuanced understanding of them as a human being. I can tell you that Neil Gaiman was born in Porchester. I can wax poetic about his relationship with Tori Amos, the inspiration for Delirium. I have read The Sandman Companion cover to cover. I love that Sandman introduced me to fantastic realms – but these worlds did not come with a passport to throw tantrums, lob cruelties, or spread rumors when something he does fails to line up with my vision. Fandom is not about that – or, I don’t want it to be.

Being a fan means having something that means something to you, as well as many other people – that is the beauty of it. It does not have to mean the same thing to everyone, or even you – nor does not mean you have to agree with every choice the creator makes. he shape of your fandom may change, but that does not diminish its power. Real fandom love is stronger than that.