By Raizel Liebler

So what does the O’Bannon decision regarding student athletes being possibly paid mean? If you are in control of sports in any way, nothing good – and therefore the decision will be appealed. But for student athletes, this is another step in the process to ensure that they are properly compensated for their efforts that previously have led to only others getting directly paid.

Let Me Introduce …

So before I go further, I need to point out that I co-wrote an article with Bill Ford – Games Are Not Coffee Mugs, 25 Santa Clara L. Rev. 1 (2012) also previously written about here at TLF, that said that games manufacturers, including video game makers, generally shouldn’t need to pay to include athletes in their games. I stand by the argument that under the First Amendment, the analysis used for real people in games should follow the same analysis as other creative works such as books and movies. To be highly simplistic, if there can be an unauthorized bio or biopic without legal problems, there should be able to be an equivalent unauthorized game. Our argument wasn’t accepted by either circuit court that considered this issue after the article’s publication. (Hart, 717 F.3d 141 (3rd Circuit 2013); Keller, 724 F.3d 1268 (9th Circuit 2013)) In response to Hart and Keller, Tyler Ochoa says

“the fact that courts cannot yet articulate a consistent First Amendment standard that distinguishes between the literal depiction of a celebrity in a sports-simulation videogame and the literal depiction of a celebrity in a more traditional work of entertainment strongly suggests that courts simply do not place the same value on the videogame medium as they do on more traditional media.”

But this doesn’t mean that student athletes should be left out in the cold. They work hard – whether or not their labor is seen as employed work or student work. As part of our forthcoming article about social media and employment in Pace Law Review in their symposium issue about social media and social justice, Keidra and I write about how the social media limitations on student athletes imply that they are both students and employees – and the limits are set based on protecting the “brand” of the sports team/ university.

With the Hart and Keller decisions regarding the need to license the personas of athletes, there was a distinct trend in how courts (and administrative bodies) viewed the rights of athletes, especially student athletes. The Chicago branch of the National Labor Relations Board ruled in a decision that is being appealed – that student-athletes, specifically the football players at Northwestern University, are employees. I don’t think that this was a politically based decision; instead, whether someone is a employee for NLRB purposes is highly checklist based.

Within a recent This Week in Law (at about the 1h:30m minute mark in episode 268), Lateef Mtima discusses the trend of cases, and how it fits within a larger social justice movement for student athletes.

So what is O’Bannon really about?

All the way back in 2009, former college basketball star Ed O’Bannon filed a class-action lawsuit for former college athletes against the National Collegiate Athletic Association (“NCAA”).

O’Bannon claimed that the NCAA violated the Sherman Antitrust Act when it exploited student athletes by not paying them anything when it used them in video games, television broadcasts, advertisements, memorabilia, and more. He argued that the NCAA eliminated any market competition for the publicity rights of student athletes, artificially keeping the price that athletes could charge for their likeness at zero.

So how could the price be zero? The NCAA requires student athletes to sign a contract if they want to play, “Form 08-3a,” giving the NCAA permission to use the student-athletes’ persona in order to promote NCAA stuff. Because no student athlete has power to negotiate any aspect of this contract, O’Bannon argued that the contract is a contract of adhesion and therefore is unenforceable.

The Decision: Taking Your Talents to Any College Team Is Receiving A Unique Bundle of Goods And Services

In the decision at the District Court for the Northern District of California, Judge Wilken went through a whole series of issues in the almost one hundred page decision.

She states that the college teams are in competition with each other to recruit the best high school basketball and football players, offering them “unique bundles of goods and services” to get players to their team, including scholarships, coaches, and “opportunities to compete at the highest level of college sports, often in front of large crowds and television audiences,” but to get this, sports “recruits must provide their schools with their athletic services and acquiesce in the use of their names, images, and likenesses for commercial and promotional purposes.”

Videogames and the Student-Athlete

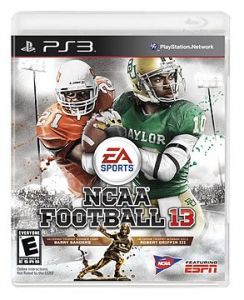

In regards to my other important interest in this case – videogames – the decision talks about the sublicense market for student athletes’ names, images, and likenesses in videogames. The opinion states that, but for the limitations imposed by the NCAA, like “television networks, videogame developers would seek to acquire group licenses to use the names, images, and likenesses of [some college student-athletes].”

The opinion sharply critiques the argument of the NCAA’s claim that there is no demand (which the NCAA based on its own ending of licensing!), stating that “the evidence presented at trial demonstrates that, prior to this litigation, the NCAA found it profitable to license its intellectual property for use in videogames.” Additionally, the athletes in the game were clearly based on the real life athletes in EA games “featur[ing] playable avatars that could easily be identified as real student-athletes despite the NCAA’s express prohibition on featuring student-athletes in videogames.”

Survey This?

The opinion also takes a dig at the survey data of sports fans: the survey was incomplete because it “did not ask respondents for their opinions about providing student-athletes with a share of licensing revenue generated from the use of their own names, images, and likenesses.” Or about other issues including colleges covering student-athletes for more than their pure cost of attendance.

What Drives Sports Fandom?

Is what drives sports fandom the NCAA’s restrictions on student-athlete compensation, as the NCAA argues? That argument doesn’t pass the non-sports fan judge test.

Instead fans are interested in being fans for other reasons, including “feelings of ‘loyalty to the school,’ which are shared by both alumni and people ‘who live in the region or the conference.’” This is true especially for national championships, such as fandom for “the NCAA’s annual men’s basketball tournament stems from the fact that schools from all over the country participate ‘so the fan base has an opportunity to cheer for someone from their region of the country.’”

Economics and Are Student-Athletes Actually Students?

There is lots of meaty goodness that reveals how much student-athletes are used for their labor, including how being students is hardly a priority for the educational institutions that are supposed to be educating them. If you are interested in social justice, there is much for you here.

What Does This Mean for Your Weekend?

If this ruling survives appeals, it will mean that student-athletes will receive at least some money for their labor, which before this ruling only made money for others. The decision will be appealed to the Ninth Circuit – the court that decided the Keller decision. The Ninth Circuit is large and the potential judges on the panel have a variety of viewpoints.

While the decision is appealed, teams will need to pay student-athletes for using their labor (because the applicability of the decision has not been stayed). Some commentary has already mentioned that players won’t be paid very much – as low as $5,000. But like the Northwestern NLRB case where the player who brought the case will not reap the rewards, the larger issue is one of social justice for student-athletes as a whole, rather than dealing with their treatment on an individual basis.

For an economic lesson on underpaying of athletes as individuals, check out this Planet Money podcast about how LeBron James (pre-move back from whence he took his talents) is underpaid.

Hey, Look, A Judge Judged Something Using Her Judge Skills

One final note: While writing this, I obviously wasn’t the first to write something about this case, but I noticed a really bizarre note in much of the coverage: Judge Claudia Wilken is not a sports fan. And during the case, sports terminology needed to be explained to her. This was an antitrust case, so like any other antitrust case – and many other civil suits there were lots of terms of art, known to those in the field, but not known to those with no previous knowledge or interest in the field.

So the hardy, har har, dudebro chuckleness about how she doesn’t already know about this is especially misplaced. In the United States, we are still arguing about whether there should be specialized courts for patent cases, so even the hint that this case needs a judge with specialized knowledge is ridiculous. We expect judges to be able to discern important issues and consult with the experts of the parties and sometimes independent experts regarding needed knowledge. What if she had been a sports fan? Would the parties have attempted to excuse her for being “the biggest fan ever” of the Terran Piggers? This is an instance where supposedly completely pure objectivity regarding the ruling is theoretically possible (at least more so than someone who cares what happens to “their team”), but instead of being praised for objectivity, she is …. critiqued for asking questions that help with her decision-making.