By Raizel Liebler

At the point that it seems like everything has been franchised in media, from public domain works like Sherlock Holmes, to Star Wars, to Angry Birds. But the cultural production — and continuity issues involved — are rarely analyzed outside of tight-knit fan communities. Derek Johnson’s Media Franchising: Creative License and Collaboration in the Culture Industries helps to show the process by which transmedia empires are created over time.

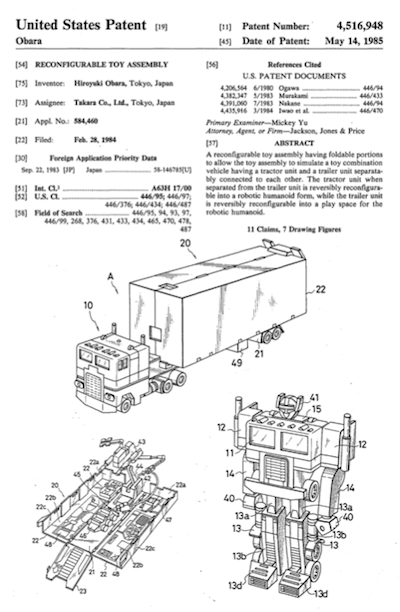

Johnson writes about several media franchises, including of greatest interest to me — Transformers and the X-Men. And despite the well-known tale of Transformers as another intrusive “made in Japan” product, the truth is much more complex, it is “an intellectual property formed in 1984 formed from a partnership between American and Japanese toymakers, and sustained since through successive reiterations across both markets — demonstrates that franchises are not only replicated products traded between and often imposed on global markets, but formatted processes whereby local franchising has fed back into an evolving transnational system of creative cultural production.” Johnson shows that Transformers is both American and Japanese — and a combination only possible through a cultural mix.

In the chapter about X-Men, Johnson discusses its rising power within the Marvel universe, and how different franchise properties “talk” or do not talk to each other. Johnston very much knows the history and interlocking X-properties — the overwhelming number of sources and canon was something that caused my fandom to wane. Issues involving overlapping interactions are also talked about about the Star Trek universe — and how new Battlestar is similar and dissimilar from the original. The process of world-building in these francises and the lines of communication and canon production are detailed well by Johnson.

Johnson is open about how his examples tend to be male-directed, an acknowledgement that is too rare in detailed examinations of popular culture. The critical analysis you are looking for on the Disney Princesses and My Little Pony isn’t in this book, but we at The Learned Fangirl will continue write about pop culture through the lens of concerns about gender and race/ethnicity!

His understanding of the importance of other franchises makes sense within context within his truly excellent introductory chapter, laying out the predecessors to his own research. As someone who always reads introductions, this is what a dissertation background media studies chapter should look like.

So are there any downsides? His lack of an overview of intellectual property could be excused, except for the mentions of franchising law — from the 1960s. And the mention of the Optimus Prime patent is cute, but shows up without contextualizing the patent in the inventor plus employer-assigned owner model that patent law exists within worldwide. A few footnotes pointing readers without a law-talking background to important sources in trademark and copyright law would help to round out this important discussion. Generally, I really want there to be more discussion between those who look at these issues from different perspectives, such as at MIT8!

Overview: A very well written book on the complex issues involved in franchising media products, especially over long time frames where continuity is important to retain fan loyalty.