by Kristin Bezio

To be fair, I did watch someone play most of the game. Many of those moments repeatedly. And if I wasn’t in the room, the plaintive “Nooooo” that would echo from the living area told me that I’d be able to see whatever it was in another ten minutes. And probably again another twenty after that. And another twenty after that.

You get the idea.

Dark Souls, and its successors, have developed the reputation of being the most frustrating game in existence. In fact, when Dark Souls 2 was announced, it was being touted by gaming journalism sites as the game in which you could “die a million times.” I always laughed at those, thinking, “okay, the game must be hard, but it can’t be that hard.”

Yes, yes it can.

The person in our house who played it is a professional game developer with years of playing and testing and designing under his belt (hint: it’s not me). This is not a game for the faint of heart or the slow of trigger finger.

He told me a few days in that he had intended to play slowly and carefully, and just not die. He gave up on that idea in less than an hour.

Among the reasons why Dark Souls is a brutal, soul-crushing experience are the following:

–Everything respawns when you die, meaning that if you’ve only just finished clearing out an area, and die to the last thing in it… yup. You get to redo the whole thing all over again!

–You lose all the souls and humanity you’re carrying when you die, which is rough. Now, you can go retrieve them from a little glowing green ball located wherever you died, but if you die on the way to it, you lose it all forever.

–So the solution is not to die, right? Well, yes and no. You see, in addition to respawning when you die, everything also respawns when you save. (Your save points and your respawn points are the same – campfires.) So when you finish that horrible garden level with the spikey trees and giant mushroom men and save… they all come back. There are some boss monsters that don’t respawn (thank god that dragon-tooth-maw-thing only dies once), but most of the common enemies will be right where you left them. Yay!

–All this wouldn’t be so bad if the enemies weren’t so difficult to deal with. The husband points out that while

individually they aren’t so bad, when three or four or six of them swarm you, it doesn’t really matter how easy one of them is to kill.

I learned about those things within the first few hours of the husband’s playthrough, and that was more than enough to convince me that attempting to play Dark Souls would turn me into a murderous harpy, and not in a good way. That said, the husband really does love the game. It lets him do a lot of exploring and resource management (it’s like Skyrim in principle, if not really like it in execution), upgrading of equipment, and tactical combat. It seems to be – as the observer – to be fairly slow-paced (not in a bad way), but that might simply be a product of the husband’s playstyle.

That said, all of the aforementioned reasons why I won’t be playing Dark Souls provide a challenge that many players have very obviously found intriguing, entertaining, and fun. More power to them.

There are some really interesting mechanics that appear in Dark Souls that don’t usually factor into most single-player games, because they’re really multiplayer components incorporated into singleplayer:

–Players can write messages to each other across the game ether. This is actually kinda cool. The game doesn’t tell you at first that these messages are (or might be) from other actual people. But as you travel through the world, players start to warn each other about hidden enemies, loot they can pick up, and strategic tips on how to kill that giant dragon on the cliff (ranged attack, the note says). These hints can be erased and up or downvoted, too, so that people are encouraged to be useful or at least funny.

–Players can ghost into each other’s games, so that from time to time you will encounter a ghost that does nothing to you (the ones that hurt you aren’t other players), but usually has some really cool gear. It’s a reminder that you aren’t alone in the horror that is the Dark Souls experience.

–If they choose, players can even pay to enter other players’ games and attack them, although this costs resources and is only available if both players have “agreed” to let it happen by choosing to become “human” (players are undead by default, and can lose their humanity by dying).

There are advantages – and disadvantages – to playing with “humanity,” and it is a resource that can be gained and lost throughout the game. In addition to being subject to attacks from other players, playing with “humanity” enables the player to summon aid – that of other players and that of AI placed strategically around the world. The inclusion of “humanity” in this capacity is not only mechanically interesting (and exciting), but produces interesting commentary on the developers’ view of human beings. Possession of “humanity,” that thing that is unique to human beings, enables us to be both our best (helpful) and worst (hostile) selves; only by embracing the polar opposites contained within the mechanic can we be considered human. Without “humanity,” players in Dark Souls must walk the game’s path alone – they will not be able to summon allies to help them – but they will also not place themselves at risk from attack by other players. The best and the worst of being human.

One of the other components that the husband likes and that I don’t is the fact that there is functionally no plot, no complex narrative. The game has more of a premise than a plot, really, and a lot of it is shrouded in mystery. Mystery can be a good thing. I loved it in Braid – the game didn’t tell us what was going on, it let us figure it out as we went. I just like some narrative to make me care about my player-character, and Dark Souls doesn’t really have that.

Partway through the game, the husband became convinced that Dark Souls was in some way aping the premise of Shadows of the Colossus: that his player-character is in fact evil and is killing off guardians in his desperate attempt to once again become human. The fact that the player-character begins as undead and is collecting “humanity” may have had something to do with this idea.

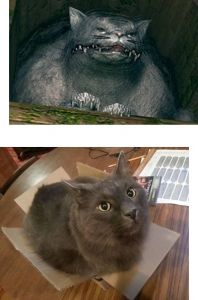

Interestingly, most of the monsters one battles appear to be giant versions of animals – really badass animals.

But the creepy resemblance of a fantasy videogame creature to my pet aside, the game feels as a whole very much like a version of Through the Looking Glass, at least to the outside viewer. Perhaps it’s because the similarity of the things in the game to things outside the game – but with a twist. Trees will slowly walk to the side to reveal hidden entrances, but otherwise appear like normal trees, the creatures that are big but otherwise just a little bit off… and the fact that the other speaking characters in the game seem like a little bit (or more than a little bit) mad…

Despite this, the game has a good deal of logic that is often absent from games. In one castle, there is the requisite corridor down which a large boulder rolls, squishing the player who gets in the way. But unlike in most games (and Indiana Jones movies), Dark Souls follows the boulders through – it later shows the player not only the mechanism by which the boulders are thrown down the corridor, but even has a giant pulling them from a large pile and dropping them down a chute into the mechanism. In other words, in Dark Souls everything has an origin, an explanation, a mad logic of its own.

One of the other distinctive parts of Dark Souls is the game’s refusal to supply a player with a standard experience; in most games, the majority of players will see the same things; acquire the same loot, weapons, and armor; fight the same enemies; and follow the same pathways. In Dark Souls this is not the case. Certainly there are many common things across different playthroughs, but there are also certain scenes and loot that only appear under specific circumstances. There are others that randomly appear for different players: the Mask of the Mother/Father/Child, for instance, will be one of the three, chosen at random for the player when a three-headed enemy is defeated. In some rare circumstances, a player may be able to acquire the other masks later (if they have accomplished certain tasks when the monster is defeated), but most players will only ever see one. This is a way for the developers to gain replayability (players will want to play again), but it also virtually guarantees a unique personal experience – and generates discussion between players, thus creating a sense of community.

In terms of the game’s narrative… well, there just isn’t much. Even the ending is ambiguous – have you just [spoilers] destroyed the world? Saved it? Replaced the guardian of the fires? Destroyed yourself? It’s not terribly clear. It isn’t even clear whether you – as the player-character – are good or evil, which I actually find rather intriguing. But the Alice in Wonderland-esque sense lasts even to the end of the game, leaving you as the player rather confused about which worlds were “real,” which undead, and whether any of them really mattered at all. It causes the player to be confused, certainly, but also provides an opportunity to reflect on the nature of the choices made throughout the game – it’s uncertain which actions are good, which bad, which neutral, and whether any of them ultimately made a difference. In short, it seems to be a game about the oddity and, ultimately, futility of life.

[Major spoilers] In fact, once the credits roll, the player ends up back where they started – in the Undead Asylum. This time, though, with all the armor and weapons and upgrades they earned in the first playthrough. Perhaps a commentary on reincarnation, or the idea that we have to keep reliving our lives – day by day – until we get “it” right, whatever “right” is. Is this a hopeful message or a depressing one? That all depends on perspective, I suppose.

In the end, the husband and I disagree about this game because although I do concede that it is carefully, deliberately, and diligently crafted, I have absolutely no interest in playing it. It doesn’t appeal to the things I look for in a game – narrative complexity, gameplay that is challenging without being frustrating or punishing – even though it does do several things I do find appealing – gameplay woven into the (sparse) narrative rather than being tangential, rich world-development, logical structure of gameplay and player-character choices. It appears to be a good game, just not one I want to play.

The husband, however, has become what one might call obsessed. The detail of thought that went into the mechanics and gameplay is enough for him – he’s a gameplay junkie who doesn’t really care much for narrative at all. And for what he likes, Dark Souls appears to be the be-all-and-end-all. It’s crafted, not just built, and has a level of detail that one generally only finds in a master creator. The logic of the puzzles, the smoothness of gameplay, the “easter eggs” that are not shoved forcefully in the player’s face but built seamlessly into the rest of the game… These things are balanced against one another and the game’s difficulty such that a player like the husband who lives for gameplay will always be on the edge of failure, always so close that replaying a level is an addictive pleasure rather than (as it would be for me) a chore.

In short, this is a game for those who love gameplay for its own sake, who have no desire to be instructed in where to go or why, and who are uninterested in complex narrative or character development as the core part of their gameplay fantasies – players whose fantasies are about challenge and skill progression. Ludics over narrative. And for those players, Dark Souls is an amazing jewel of a game. Even those of us who aren’t those kind of players can appreciate and respect what Dark Souls is doing – but if you aren’t keen on riding that knife-edge of failure, if you like the story of your game to direct your actions, if character development is part of your fantasy, then this isn’t the game for you. It’s a great game, but it isn’t for everyone.

[…] You Died Again: A Review of Dark Souls by Someone Who Didn’t Play It Ha. I watched someone play this game and yeah–that’s pretty much how I feel about it, too. […]

But the narrative qualities of this game are what separates it from the pack… It’s a system not really suited for spectating, unless you really manage to soak up every design nuance

Once can also play through a game and not soak up every design nuance. The narrative in Dark Souls is so deeply buried that even a player (rather than a spectator) of the game misses most of it, at least in our household where the scope of the narrative was discovered through extensive time spent on forums and with wikis rather than through playing. I would also argue that no game is “really suited for spectating,” since the point of games is to play them, but that I got considerably more out of spectating than I would have playing this one, since I would have given up in frustration fairly early on.

Dark Souls is not a game for everyone, and I’m one of those people it isn’t for – but spectating let me see and appreciate a lot of the things about the game that I would otherwise have missed. I like my narrative overt rather than buried, and while I appreciate the craft that went into the nuance of Dark Souls, it isn’t something I would have enjoyed playing at all. I appreciate it as a spectator, but I would have hated it as a player, and I think that’s also worth pointing out.