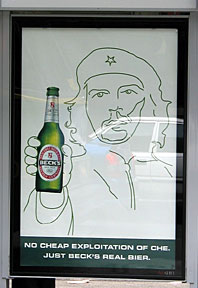

The paradox is to wield Che in an attack on [capitalism], its critics must participate in it. They engage in the act of consuming Che.

As Michael Casey describes in his excellent social history, Che’s afterlife : the legacy of an image, the meme of one captured moment in the life of Argentine/Cuban revolutionary Ernesto (Che) Guevara has an amazing cross-cultural resonance (pdf). According to the curator of a 2006 art exhibit of Che-based art, this is the most reproduced image in the history of photography.

Casey says that

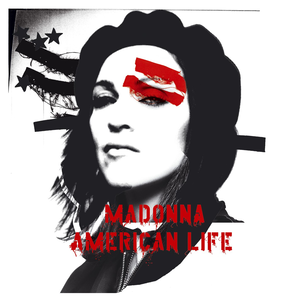

Che is now everywhere. In its common form as a two-tone abstraction of Alberto Korda’s famous 1960 photograph, his image is simultaneously a potent symbol of resistance in the developing world, an anti-globalization banner, and a favored sales vehicle among globally engaged marketing executives.

So how did this happen? The book details how while

the compelling events of his real life and the story of its violent end perpetuated his legacy, it took the mass replication, reproduction, and marketing of the Korda photo to years later transform him into a pop superstar of immense iconic pow

But this visual meme happened due to a confluence of influences:

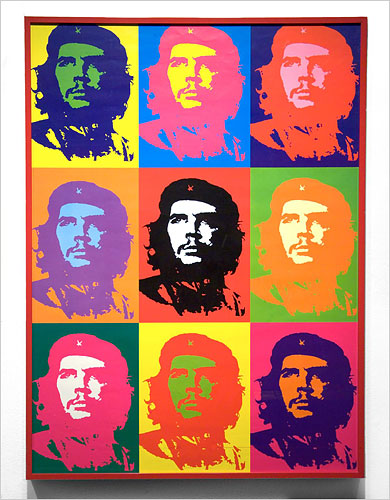

Political opportunism, the publishing industry, photography, silk-screening, pop art, graphic design, computers, the Internet, copyright laws, and consumer-marketing theories have all collaborated in the maintenance of Che’s afterlife.

The specific message of the image, however, has decreased in inverse proportion to its popularity. Viva la revolucion? Power to the people? Overthrow the capitalist pigs? Or just a dramatic, vaguely rebellious image? You decide.

This book has much to give to those interested in history, art, marketing, and the flow of culture, and especially appropriation art, but it also has lots of interesting gems regarding intellectual property — including moral rights. Because the author isn’t a lawyer, sometimes he doesn’t always use the correct law-talking terminology, but the description is vivid.

For example, Casey discusses the complicated issues surrounding the picture to the right. Taken from the Fitzpatrick art print of the original photo, an anonymous artist created a work that was attributed to Warhol — who then certified the work as authentically Warhol — even though it wasn’t!

During the preceding thirty-seven years of legal inaction, the image effectively roamed the world copyright free as producers of derivative art exploited it without paying fees. It functioned much like an open standard …it was a freely available template to which others could apply their inventive talents. This de facto public domain status facilitated an explosion of creative expression, as artists, satirists, and political commenters took to the image with glee. Some were faithful to the Cuban government’s socialist representations of Che; others not. Neither group had to worry about lawsuits.

The present situation of public domain versus ownership of the image is complicated by differing international standards concerning the copyright (Cuba had rejected copyright in 1967), trademark, and moral rights. Casey expands on how the IP-protected version of “Che” competes with the publics version of Che — and how difficult it is to undo the public ownership idea of this image.

An

Fairey’s Obama is not wearing a beret, and he’s looking left instead of right, but his face tilts at the same angle as Che’s. His jaw is set with the same willfulness and strength, and he too is gazing recognizably upward into the future …. Obama’s eyes, though, are filled not with righteous anger but with vague and lofty hope.

So that does mean that the Hope poster is really a mashup between Che and the AP photo? It seems at least it is intended to be at least evocative of our cultural memory!