by Deanna McMillan

Even when we feel as though the entire universe is accessible through our computers, there still exist some films that must be seen on celluloid.

I’m not an anti-digital luddite per se; I feel as though the medium of cinema hasn’t yet caught up with technology. A new aesthetic lost the chance to ferment before Hollywood jumped on the cost-savings bandwagon, robbing cinephiles of the underground experimentation that works best when fumbling towards new industry standards. Few digital films that I’ve seen since its advent exploit the technology to its greatest visual effect. The first two that come to mind are Black Swan and We Need to Talk About Kevin. And films like Public Enemies, with its early adoption of the digital format, contained the visual hallmarks of stinky amateurism with its light bleed and pixelated appearance, which worsened an already anachronistic film premise. I love the democratic potential of cheap, accessible digital cinema, but its typical use still hurts my precious pupils.

Most of the films I will discuss on TLF will be those seen on celluloid, a rare treat these days. But I also plan to write about films that can be seen easily in digital or streaming formats, often arguing why those films should only been seen in their original format.

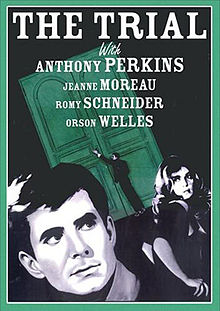

A perfect example of the latter is Orson Welles’s 1962 adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial:

This film, which I would rank near Citizen Kane as his best, has the misfortune of being in the public domain–which makes it readily accessible but of little interest to film preservationists. (A similar fate befell Welles’s Confidential Report until the Criterion Collection issued the Mr. Arkadin box set.) Studio Canal did reissue the film this year in a remastered Blu-ray edition – but only in Europe, so much of what I have to say about the picture still applies.

As one can see from the YouTube and all the region-free DVD versions of the film, they have horrid, murky image quality; some have been tinted, and they’re all eyesores. I had the privilege of seeing The Trial two years ago at the Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University in a 35mm archival print, a mere few months after streaming it.

The difference was clear: Seeing The Trial again in a scratchy but otherwise crystal clear print in a semi-proper film auditorium proved revelatory, the only way to watch the film. The crisp chiaroscuro, the brilliant editing juxtapositions of ultra tight and overwhelmingly wide shots, and the decrepit abandoned buildings used for shooting in lieu of a soundstage created an atmospheric, nightmarish backdrop on accident. This visual impact disappears on the digital versions of poorly preserved copies, leaving all the scenes hazy at best, indecipherable at worst. I will not analyze the performances here, as those can be discerned even in the crappiest print of the film. The Trial ranks among Welles’s best films and should be treated as such through proper restoration and distribution, because it can’t be rediscovered if it looks like shit.

Bonus link: Filming The Trial. Welles talks at length here about how he made the film:

Black Swan was shot almost entirely on film, as was We Need to Talk About Kevin. That’s probably why they’re the only digital movies you’ve seen that looked good – they aren’t digital.

“the visual hallmarks of stinky amateurism ” <-This made me laugh out loud. Now I have to read everything you've ever written.